“After radiation is better understood a day will come when the power from exploding toms will change the whole world we know. Some of the mutations will be good ones – wonderful things beyond our dreams – and I believe I believe this with all my heart, THE DAY WILL COME WHEN MANKIND WILL THANK GOD FOR THE STRANGE AND BEAUTIFUL ENERGY FROM THE ATOM.”

Tillie’s final monologue from “The Effect of Radiation on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds”

We talked about the year 2000 in high school, never imagining we would live long enough to see it. There was no imagining back then the technology, the Internet, and other strange behaviors of this decade.

Very few people I talk to remember the movie, “The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds,” a play from the 60s with a film adaptation in 1971. The movie was directed by Paul Newman and starred his wife, Joann Woodward, and daughter, Nell Potts.

The gist of the play had little to do with gamma rays or Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds and more to do with dysfunctional families. But somehow, the title stuck with me.

What, pray tell, does this have to do with St. Mary’s Hospital in Rochester, Minn.? Well, Dr. Pollock specializes in Gamma Knife Radiosurgery, and there I was checking into the hospital the day after we discussed the tumors in my brain.

He did not recognize the movie but mentioned that Bruce Banner turned into the Hulk after exposure to Gamma Radiation. I asked if I would be able to use my brain to break light bulbs and move objects with telekinesis like John Travolta in “Phenomenon.”

They looked at me like I was crazy. “How about glow in the dark?”

I watch too many movies.

Checking into the hospital at 5:30 a.m. meant checking out of the hotel at that ungodly hour of the morning. We had to go through security, and I gave up my pocket knife because I was honest about having one buried deep in my bag.

We were escorted to a waiting area and in a few minutes whisked away to a room to be prepped for the procedure. It’s one thing to have something explained to you — quite another to experience it.

There was the usual blood pressure, weight, temp, and questions. They accessed my power port for IVs and a dose of Ativan. Thank goodness for Ativan.

JC waited in the waiting room, and received multiple text messages updating my progress. The next part I had to do alone.

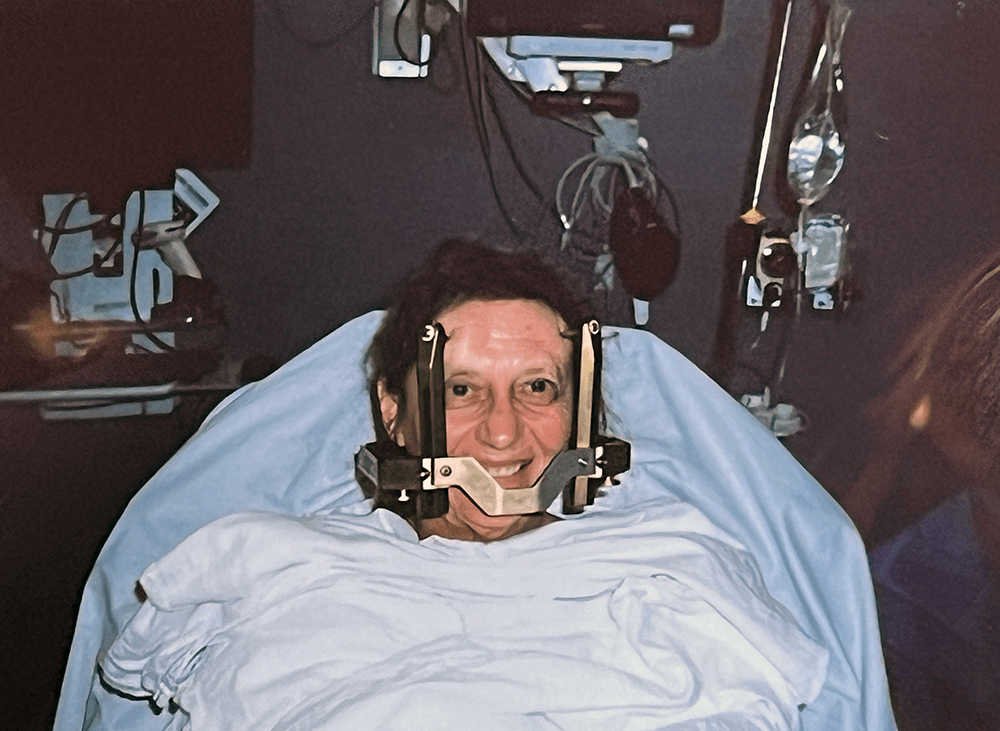

Gamma Knife surgery targets tumors with multiple rays of radiation that meet at the source of the tumor, and then “boom” the tumor explodes (my words). To protect the brain and ensure the accuracy of the radiation, the patient (me) had to be fitted with a frame — a lightweight box — over my head — screwed into my skull so it would not move during the procedure.

Remembering that moment makes this difficult to explain but here goes.

It took three people, the doctor and two nurses on either side of me. Dr. Pollack and one nurse to attach the frame and one nurse to hold my hand.

First, two rods were placed in my ears to level the box. I asked them how they could assume my ears were on my head straight. No problem.

The box was balanced on the rods. Next, working simultaneously a syringe with numbing agent was injected into four areas on my skull, two in front and two in back.

“Close your eyes,” the nurse with my hands said. It was streaming down my face. Without waiting for more than a few seconds, they began to gather the screws. It reminded me of the tiny brass screws on a vintage glass light fixture that you tighten after you replace a light bulb to hold it in place.

I’m not going to lie, the crunching sound was painful, and thankfully, I was drugged up. “Did I break your finger,” I asked the nurse. “No,” she said, “You had two of them.”

As strange as this might seem, the nurse had a Polaroid camera and did not hesitate to take my photo when I asked. If you see I’m smiling in that picture, it is because of the drugs.

Everything that happened next required two people to guide the box, with my head, into its proper place in the MRI machine and then the Gamma Knife tube, which was similar. I vowed I would not be claustrophobic in that tube and was fully prepared to sing if I had to distract myself. It wasn’t a problem — I slept for the entire 90 minutes.

By 11 a.m., with my head wrapped in gauze like an injured soldier in some Civil War movie armed with ice packs, we were discharged from the hospital and headed home.

It’s been about seven weeks since that day. Today we look at what effect the Gamma Rays had on my brain. I didn’t turn green, experience superpowers or glow in the dark. I do, however, feel like the Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds exposed to the greatest amount of radiation — spindly and thin, searching for the sun.

Leave a comment